Fly By Wire - Leave the Cables Behind

Fly by Wire is when the pilot delivers physical inputs via control devices which in turn are connected to flight control surfaces. Fly by wire removes the physical connection, but in a good way.

To control the aircraft. She does this using the “yoke” or “side-stick” (depending on aircraft type) as well as peddles and console devices. In modern aircraft, this is done by fly by wire.

Fly By Wire

In aircraft like the Boeing B737, these cockpit controls are connected “directly” via cables to these devices. But in other aircraft, such as the Airbus A320, they are not physically connected at all.

Instead relying on wire systems between the pilot inputs and the actuator device. Thus “fly-by-wire” uses electrical cables to transfer the inputs between pilot and control surfaces as well as the surface feedback. The main reasons? Weight and costs.

Wire Systems Controls

Formula one cars recently took on brake-by-wire. You may have read about it. And it’s easy to understand why. G-forces, speeds and physical limitations of the human body limit the amount of force the human foot can apply. Just like power steering, we need some mechanical way to help us when we need force.

And don’t worry. A wire control failure or electronic signal malfunction will not stop Airbus pilots from controlling their aircraft. There are several recovery modes available to them, including a backup physical connection to critical systems.

The Wright Flyer

On Kill Devil hills way back in 1917 Wilbur and Orville figured out how to control these new-fangled airplanes.

Amongst other novel applications, these bicycle makers designed the first aircraft flight control system. From his seat, Orville used piano wire to control “warped wings” so that lift was controlled. This was possible because the Wright flyer was a small, light aircraft made from balsa and cotton sheets.

An F-22 Raptor at 60,000 ft in a 5-G banked turn is a different story. Here you need electronic control from the pilot’s control stick to the flaps. Otherwise control is impossible.

The forces acting upon the control surfaces of that aircraft simply do not allow it. This is the same for commercial pilots. They cannot control the aircraft without mechanical assistance derived from actuators via cockpit signals.

Weight Vs "Feel"

Have you noticed when you park your car the steering wheel moves easily? Softly turning from left to right and vice versa? But at 100mph, on the motorway, it’s firmer to the touch.

A driver must use significant effort to turn the car even gently. Car designers have ensured that the “feel” of the wheel corresponds to the forces at work. So that you don’t lose control.

Commercial aircraft also have “feel” devices. One for low speed and one for high speed, just like your Audi. A pilot must feel through the control column the approximate forces relative to the aircraft’s current configuration, speed, and attitude.

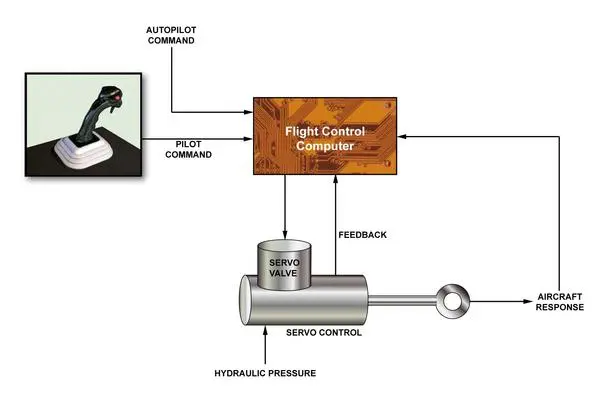

This is what allows pilots to learn how to fly. What is happening “under the hood” of wire aircraft is those actual signals are going through “feel” units. The aircraft FCC converts these from physical and digital signals. Pilots control actuators (using hydraulic controls) how much force and how fast to move the control surfaces. The FCC (Flight Control Computer) provides full mechanical flight controls in a learnable feel.

Concorde and The Weight Problem

And this was years after fighter aircraft had been doing the same thing, mostly due to the physical forces at work. But what Airbus was after was something else.

As aircraft designers, they correctly identified the fact that the pilots were all the way up at the nose of the airplane, and the control surfaces were way behind them on the wings and on the tail section. So, for pilots to control the aircraft, as with the B737, the control columns and control surface actuators are connected by cables (and via the “feel” devices).

Along with all the other protection needed to tuck them away inside the fuselage and wings.

And they had to do this twice – for the Pilot and Co-pilot. And make sure they were completely independent for redundancy from failure. But Airbus knew if they could do away with all of that they would save a lot of weight. And when you save weight you either add payload (good for the customer), increase the range (great for the customer!), or just improve fuel efficiency (superb for the customer).

Fly By Wire and Aircraft Safety

You are still not convinced. We can tell. If you’re out walking your golden retriever using a dog-by-wire device designed to stop him from running away, you really are going to need some convincing that he’s not going to, well, just run away.

We got good news. Electronic Interface devices are more reliable than conventional controls and thus wire technology is safer. Because they are smaller, lighter, and easier to install we can make sure there are more of them in our flight control systems.

The Digital Flight Control system is also less likely to break, needs less maintenance, and won’t corrode or be affected by the environment. Here’s something you also might not be aware of – everything else on the aircraft is under digital control already.

Take the engines. The FADEC unit or ECU (engine control unit) is a small box of tricks that sits on the engine casing and takes instructions not from the pilot, but from the FCC (flight control computer). The range of needs and data required by a modern jet engine far exceeds the capability of a busy pilot trying to fly the aircraft and so the digital flight control system does most of the heavy lifting.

Autopilot is also a digital system as is the trim system. Every critical system in the aircraft is controlled digitally including airborne devices that allow air traffic control.

If you are happy with this – which you should be – then you should be happy with the fact that the flight controls are also digitally controlled by fly by wire. But if you’re the kind of person that would rather everything onboard be connected by wires, cables, or anything from a Wes Anderson movie then I don’t know what to tell ya.